My visit to a waste management facility!

Have you ever wondered what actually happens to your refreshing bottle, can, or carton of One Water after you’ve finished it?

All of our products are 100% recyclable, so when you take that final sip and pop your bottle in the correct recycling bin (we’re counting on you!), it embarks on an exciting journey to a new life.

I recently swapped the comforts of the office for a high-vis and a hard hat and immersed myself in the world of waste at the Southwark Materials Recovery Facility (MRF), and the Beddington Energy Recovery Facility (ERF).

The experience was truly binspirational (sorry!), so let me walk you through it…

Firstly, it is important to note that the processes of recycling collection, sorting and processing vary across the country, so whilst I’m looking here at our products’ journey through recycling in south London, it might look a little different elsewhere. This is because different councils have different contracts with different waste management companies, who all do things a little, well, differently!

As of March this year, the UK government implemented new Simpler Recycling legislation to standardise the process across England and reduce confusion for household recycling in order to increase recycling rates. So, over the coming year the opportunities for customers to do the right thing with their empty bottle will increase! You might also have heard of Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR), another new piece of legislation which is generating funds to invest in recycling infrastructure across the country via a fee system for all packaging supplied to the UK market. We are big fans of collaboration and engaging with a system which inspires wider industry change – so although we are not a fan of the associated additional costs, we are looking forward to seeing the developments which take place as a result of EPR.

So, with dreams of mass recycling in mind, I headed to Southwark’s MRF, which is run by waste management company, Veolia, and processes over 1 million tonnes of waste every year! Lorries across Merton, Sutton, Croydon and Kingston collect recycling from recycling bins – including individual household kerbside bins and public recycling bins – and bring their contents to the MRF.

Step 1:

The lorries are weighed before making their way to the tipping hall, where they tip their contents onto the floor for a visual inspection. One of the single biggest problems for recycling facilities is contamination, so at this point the staff look for any items which should not be present and might contaminate the recycling stream.

Southwark MRF is a large and advanced MRF facility so it is well equipped to handle inputs that are contaminated with non-recyclable materials such as food waste, nappies, sanitary products, and more. However, even at this facility, if a load is deemed to be over 15% contaminated upon inspection, the whole load will be redirected to general waste so that it does not contaminate the recycling stream. The recycling stream has to maintain high quality material inputs because the better the quality of the inputs, the better the quality of the outputs which means that the materials can be reprocessed and made into other things more effectively.

This all means that it’s up to us to ensure that we are putting the right materials into our recycling bins and that they are clean and dry. So what does that mean in practice? Next time your recycling bin is full, think, would I be willing to tip this over my head? If the answer is yes, chances are you have recycled correctly! If the answer is no and you’re worried about a piece of soggy cardboard (or worse) that you put in there, you have some work to do! Check out Recycle Now to find out how to recycle specific materials in your local area if you aren’t sure!

Step 2:

Following the visual inspection, the materials are lifted into a machine called a bag splitter to make sure that any big bags of recycling are all opened and their contents can be evenly distributed across the conveyor belt. They then travel to ‘disc screens’ which sorts materials based on size: Smaller items fall through the discs, while larger items are carried across the discs for further sorting by material. This is why it is so important to read recycling instructions on any packaging. For ours, it’s really important that caps are left on (as instructed on the bottles), so that they are more likely to reach the correct material stream and not get lost!

One of the biggest problems faced by this MRF is the presence of ‘flexible plastic’ e.g. plastic bags, bread bags, cling film etc, in the recycling stream. These are not recyclable through normal kerbside services. The plastic gets wrapped around the spinning disks and causes the machines to break down. So, reusable shopping bags are the way to go and for now, check the best place to recycle flexible plastics locally using the Recycle Now website (normally large supermarkets). You might be thinking that this doesn’t seem very efficient, and it’s not – not everybody will take their flexible plastics to the supermarket to be recycled so a lot of it ends up in general waste. But in comes that new legislation I mentioned earlier! Under the new Simpler Recycling legislation, flexible plastics such as plastic film will soon also be collected in the plastic waste stream, meaning that traditionally ‘hard-to-recycle’ items such as food packaging will become easier to recycle – hooray!

Step 3:

The materials are then sorted by hand and any materials that should not be present are removed from the conveyor belt. Then the excitement really begins, as an array of impressive machinery is put to work identifying different materials and separating them.

Cans A giant magnet over the conveyor belt attracts the steel cans, which then fly off the conveyor belt and join the steel stream. An Eddy Current Separator (ECS) then separates non-ferrous metals such as aluminium from the other materials. A One Water aluminium can will ‘jump’ off the conveyor belt as the ECS introduces currents that cause conductive materials to be repelled from the non-conductive materials (eg. paper) around them. The aluminium can then joins its friends in the aluminium stream, one step closer to its new life.

A giant magnet over the conveyor belt attracts the steel cans, which then fly off the conveyor belt and join the steel stream. An Eddy Current Separator (ECS) then separates non-ferrous metals such as aluminium from the other materials. A One Water aluminium can will ‘jump’ off the conveyor belt as the ECS introduces currents that cause conductive materials to be repelled from the non-conductive materials (eg. paper) around them. The aluminium can then joins its friends in the aluminium stream, one step closer to its new life.

rPET

If that wasn’t cool enough, now the lasers come in… In technical terms, a machine using near-infrared (NIR) spectroscopy is used to distinguish between plastics, paper and other materials by analysing the infrared spectrum of each item as it passes down the conveyor belt. In simpler terms, a special laser identifies plastic on the conveyor belt and a jet of air blows it across to a new belt; it’s like a rollercoaster for our rPET bottles! Did you know, recycling saves between 30% and 80% of the carbon emissions that virgin plastic processing and manufacturing generates? We only use 100% recycled PET for our bottles, but the planet desperately needs more companies to do the same.

Cartons

Our Tetra Pak cartons, which are made from mostly FSC certified paperboard, are often considered harder to recycle than other materials. This is because, while they are 100% recyclable, not all local authorities collect these cartons kerbside because they contain a few different materials – so you might have to take them elsewhere to be recycled. As of April 2026, England’s Simpler Recycling reforms mandate that liquid cartons must be collected at kerbside for recycling, and this will be made clear on the packaging. And of course, don’t forget to keep the cap on when you recycle them!

At Southwark MRF, cartons are sorted by a mixture of technology such as optical sorting systems, and they are contained all together ready to be sent to Halifax, where the UK’s dedicated Tetra Pak recycling facility is located. Here, the cartons are loaded into a large pulper and blended with water which separates the paper from the aluminium and plastic polymers. The paper fibres are then cleaned, pressed and dried and formed into paper rolls which can be used to make a variety of products such as paper towels and cardboard boxes. The aluminium and plastic polymers are shredded together and turned into granules which can also form part of various products such as pallets, crates, and even furniture!

Glass

Glass is broken down by various machines in the facility into small glass pellets, which reach 99.9% purity after processing. At the Southwark MRF, Veolia has a contract with a local insulation company, Knauf Insulation, who purchase these glass pellets and use them to make their insulation, with their glass mineral wool containing up to 80% renewable materials overall. This closed loop solution ensures that the glass that gets recycled is repurposed so no new glass made from virgin materials needs to be produced for Knauf Insulation’s operations! Across the country, all recycled glass gets washed, crushed, sorted by colour using lasers and sensors, and melted, ready to make something new. This process can be energy intensive, but overall it is a significant energy saving compared to producing glass from virgin materials, and glass can be recycled endlessly without losing its quality. So make sure you get those bottles into the recycling bin!

Step 4:

Back to the MRF, what happens next?

The sorted materials such as plastic, paper and aluminium are compressed into neat bales so that they can be efficiently stored and transported to different facilities for reprocessing. It’s very satisfying stuff. One person’s trash really is another’s treasure – especially when it’s been expertly sorted, baled, and ready for its next life.

Step 5:

This bit gets quite technical but it’s where the magic really happens.

rPET

The bales containing plastic material are transported by lorry to a dedicated conversion facility (e.g. Veolia’s Plastics Recovery Facility in Dagenham), where the bales are unloaded and uncompressed upon arrival.

The plastic is then fed into enormous shredders which create fine flakes of plastic material. This makes a homogenous mixture which facilitates the separation of different plastic types. Then it’s bath time for the plastic flakes(!) which are cleaned in an industrial washing tank and then moved into a separation tank powered by paddle wheel systems. In this tank, low density plastics such as from bottle tops like ours (made of LDPE), float and collect on the surface of the water, whilst denser plastic materials sink to the bottom where they are then collected.

Next, the flakes are rinsed again, dried in a centrifuge, and the impurities are removed by suction and an optical sorting system. Then the purified flakes are stored in silos based on category and their chemical, physical and mechanical properties are studied in the laboratory to ensure that the materials meet clients’ requirements.

The flakes are now fed into an extruder (a machine which heats and shapes materials) before being cut into granules which are then dried again, stored, and inspected once more to ensure the material complies with technical specifications and regulatory requirements. Then it’s sent off to clients who will use the granules to make new products. (If you’re still reading, well done for making it this far!)

To summarise: the plastic is shredded, washed, separated, dried, filtered, stored, studied, heated, softened, cut, dried, stored, inspected, and distributed. Blimey! What is important to note is that, despite the complexity of this process, producing recycled plastics requires approximately 75% less energy than producing new virgin plastic polymers, with CO2 emissions reduced by around 60%. It’s bincredible stuff (sorry again!).

So if you put your One Water rPET bottle in the recycling bin, it will probably come back as another bottle! This won’t happen in an endless cycle as unfortunately the quality of plastic does degrade each time it is recycled. But don’t worry, the material doesn’t get wasted. Once the material has degraded and can’t be reprocessed into another bottle (estimates suggest this is the case after around 10 times of recycling the bottle), the material will be made into something else, for example it might become part of a park bench!

Cans

The final piece of the puzzle is understanding the next step for our aluminium cans. This is where we can see the true circular economy in action as aluminium is infinitely recyclable, without losing its quality!  If you ever find yourself in Warrington, Cheshire, you will find Novelis recycling. This is the world’s largest recycler of used beverage cans (UBCs) -the facility actually has the capacity to recycle every single aluminium beverage can sold in the UK each year! So if Novelis can do that, surely we can play our part in helping the cans get there. We can, you can, they can, recycle cans!

If you ever find yourself in Warrington, Cheshire, you will find Novelis recycling. This is the world’s largest recycler of used beverage cans (UBCs) -the facility actually has the capacity to recycle every single aluminium beverage can sold in the UK each year! So if Novelis can do that, surely we can play our part in helping the cans get there. We can, you can, they can, recycle cans!

Making aluminium products out of recycled aluminium, rather than mining new aluminium, can save 95% on energy use and greenhouse gas emissions, so it is incredibly worthwhile. Once the baled aluminum reaches the facility, it is cleaned and shredded into smaller pieces, much like the plastic we discussed earlier. Coatings are removed, and the material is melted into molten aluminium and purified in a holding furnace before being cast into huge ingots (large oblong shaped blocks). The whole furnace is then tipped on its side to pour the molten aluminium into the ingot casting unit, where it is treated again to remove any microscopic non-metallic particles and gases. As the metal flows into the moulds, it is chilled by jets of cold water flowing around the base of the mould, and the ingot gradually solidifies. These large blocks of aluminium are then rolled into thin sheets, ready to be made into cans once again!

What happens if we don’t recycle correctly?

So all of our products should end up in this MRF or other similar facilities across the country, and then be reprocessed. However, whilst we strive to make our products as sustainable as possible by design, their proper disposal is down to you, the consumer. If the products end up in the general waste stream rather than the recycling stream, they go on a very different journey -one which we would like to avoid.

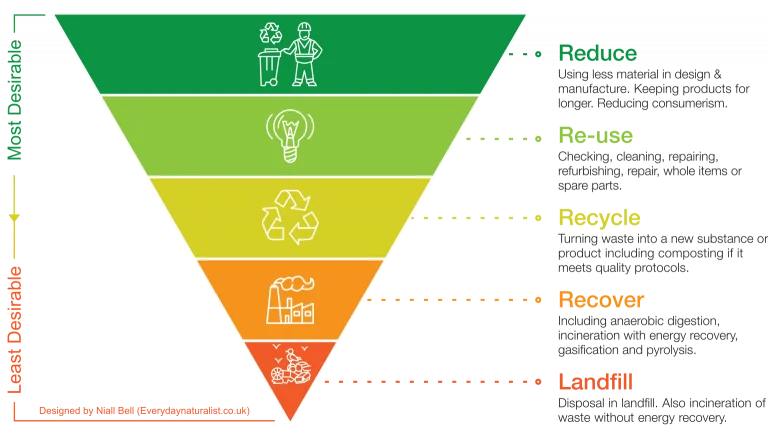

Beddington ERF is run by waste management company Viridor, and they do their best to make their operations as sustainable as possible. However, in line with the UK waste hierarchy, when it comes to looking after the environment, recycling is a significantly better approach than recovering energy from waste.

The process at an ERF

There is no sorting of the materials when they arrive at an ERF as they all end up in the enormous on-site combustion chamber which burns continuously at over 850°C. The materials are tipped out by lorries and added to the waste bunker where the waste gets mixed up by a large crane before being slowly added to the incinerator. The process of the burning produces hot gases that heat water in a boiler. This creates high-pressure steam, which spins a turbine connected to a generator. The result is enough electricity to power the facility itself and around 60,000 homes in the local area.

Before gases from the furnace are released, they go through a thorough multi-stage cleaning process. Chemicals and filters remove pollutants such as nitrogen oxides, acid gases, and heavy metals. Emissions are continuously monitored and regulated by the Environment Agency to ensure they remain within strict limits.

There are additional by-products of the process such as fine dust called Air Pollution Control Residue (APCr), which is collected and treated for reuse in construction. The heavier Incinerator Bottom Ash (IBA), about 23% of the original waste, is processed to recover metals for recycling, while the remaining material is turned into aggregate for roads and building projects. It’s very clever, but it’s not as good as recycling!

Energy recovery vs landfill

Energy recovery from waste is preferable to landfill for many reasons. Here are a few:

- Landfill releases methane while the ERF releases carbon dioxide. Both are greenhouse gases, but on a 100-year timescale, methane has 28 times greater global warming potential than carbon dioxide and is 84 times more potent on a 20-year timescale.

- As waste decomposes in landfill it releases toxins and can create leachate that pollutes the land, ground, and water. This can harm biodiversity and impact human health.

- Energy recovered from waste represents energy which has not involved the extraction and burning of fossil fuels just for energy generation.

While Viridor is striving to make the process of energy recovery from waste as sustainable as possible, it remains an energy and resource intensive process. Unfortunately, recyclable material still ends up in ERFs, landfills or polluting ecosystems, which makes us at One Water very sad. Our belief is that if you have to buy a bottle of water, buy one that does better for both people and the planet, and most importantly, recycle it!